While the world was in locked down due to COVID-19, many businesses that rely upon physical spaces have turned to virtual tours to supply a feeling of the space for users who are currently unable to visit.

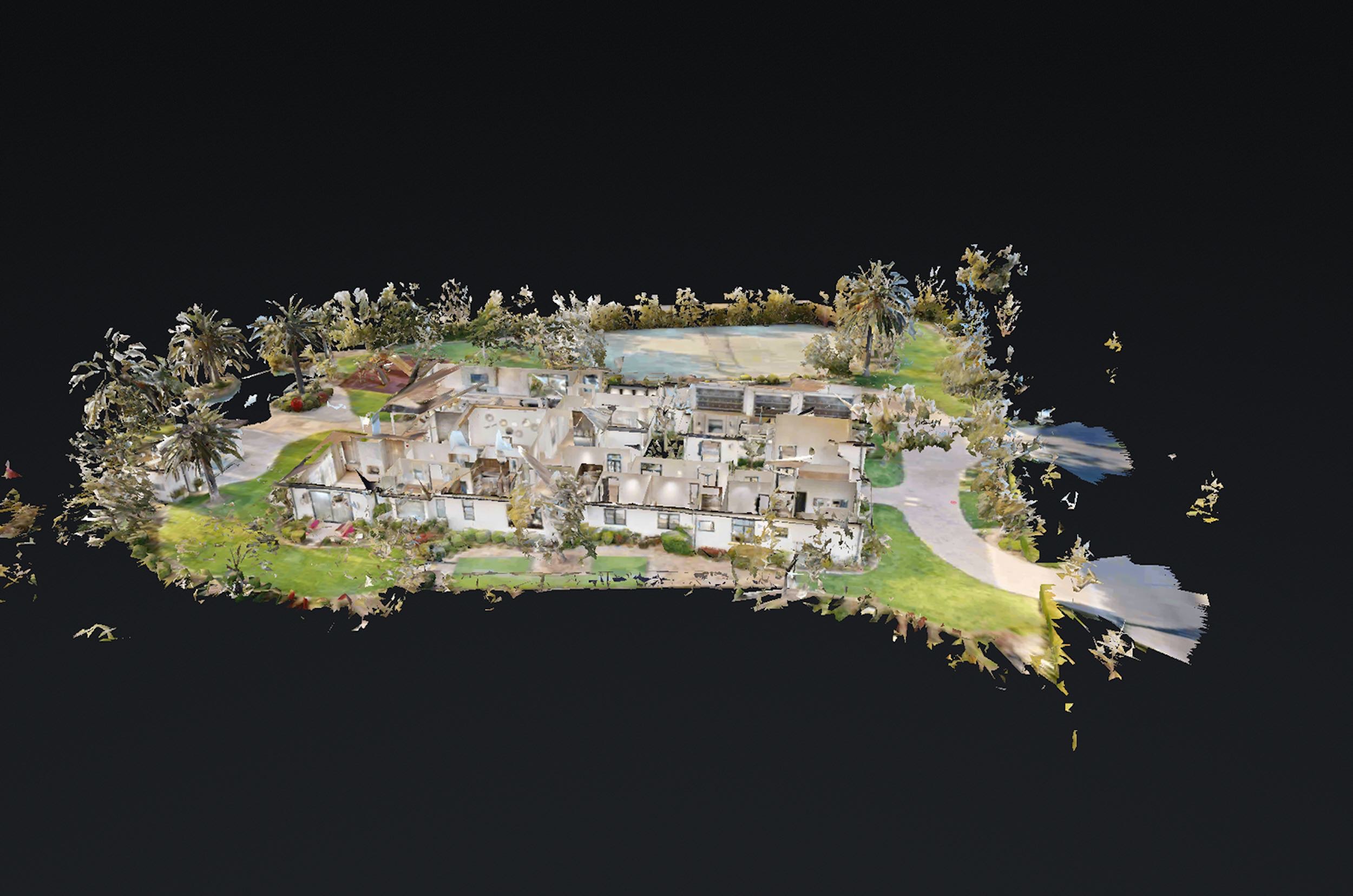

Especially in real estate, there has been a lot of current emphasis on virtual tours of homes. Many other types of business, such as cultural associations, universities, wedding venues, and much outdoor attractions, have followed suit.

This technology has been gradually maturing in the background for years, and many users have been subjected to the basic interaction paradigm through popular examples such as the Street View feature within Google Maps.

The Vatican museum’s virtual tours offer a single 360° photograph each room, but links between rooms using an arrow icon onto the floor. The National Marine Sanctuaries offers video tours shot in 360°, so the user can pan around as the movie plays but cannot proceed independently. Virtual Tours Typically Used for

Checking Details Later in the Process

In our study, users often noted the presence of virtual tours on websites that offered themand used phrases like,”if I were interested, they offer a virtual tour, which is fine.”

While the favorable opinion toward the choice to take a virtual tour was fairly consistent, many consumers then went about their business without interacting with the tour, demonstrating that they were not actually very interested (and further demonstrating one of the first rules of UX –“don’t listen to your customers, observe their behavior instead”).

Really, in many of the test sessions, users didn’t interact with the virtual tours until later in their visit on the website or when straight instructed to open the tour from the study facilitator. (A skilled facilitator will prompt participants to utilize the feature of interest only at the close of the task, to avoid bias.)

In fact, especially when the task involved gathering information for consequential decisions, such as purchasing a home, booking a wedding site, or picking a college, participants opted to interact with standard photo galleries, text descriptions, and even prerecorded video tours before using the 3D virtual tours.

Their comments revealed that they expected the virtual tours to take effort to utilize and they preferred to start by looking at photographs to decide if the property, artwork, or physical space was intriguing enough before buying a virtual tour.

Thus, like is often the case with such intricate features, users were doing an (unconscious) cost-benefit analysis of the virtual tour, weighing in the anticipated interaction price against the extra information delivered by the tour. A study participant summed this up well and said:

This preference for still photographs as the initial touchpoint was due to two factors — (1) picture galleries can be immediately swiped through to see a huge variety of views within the space within a brief while, and (2) photos afford a degree of direct access to certain details (as you doesn’t need to walk through the full house to check at a particular bedroom). As one study participant put it,

Real-estate and event-planning users often sought out virtual tours to check on details such as:

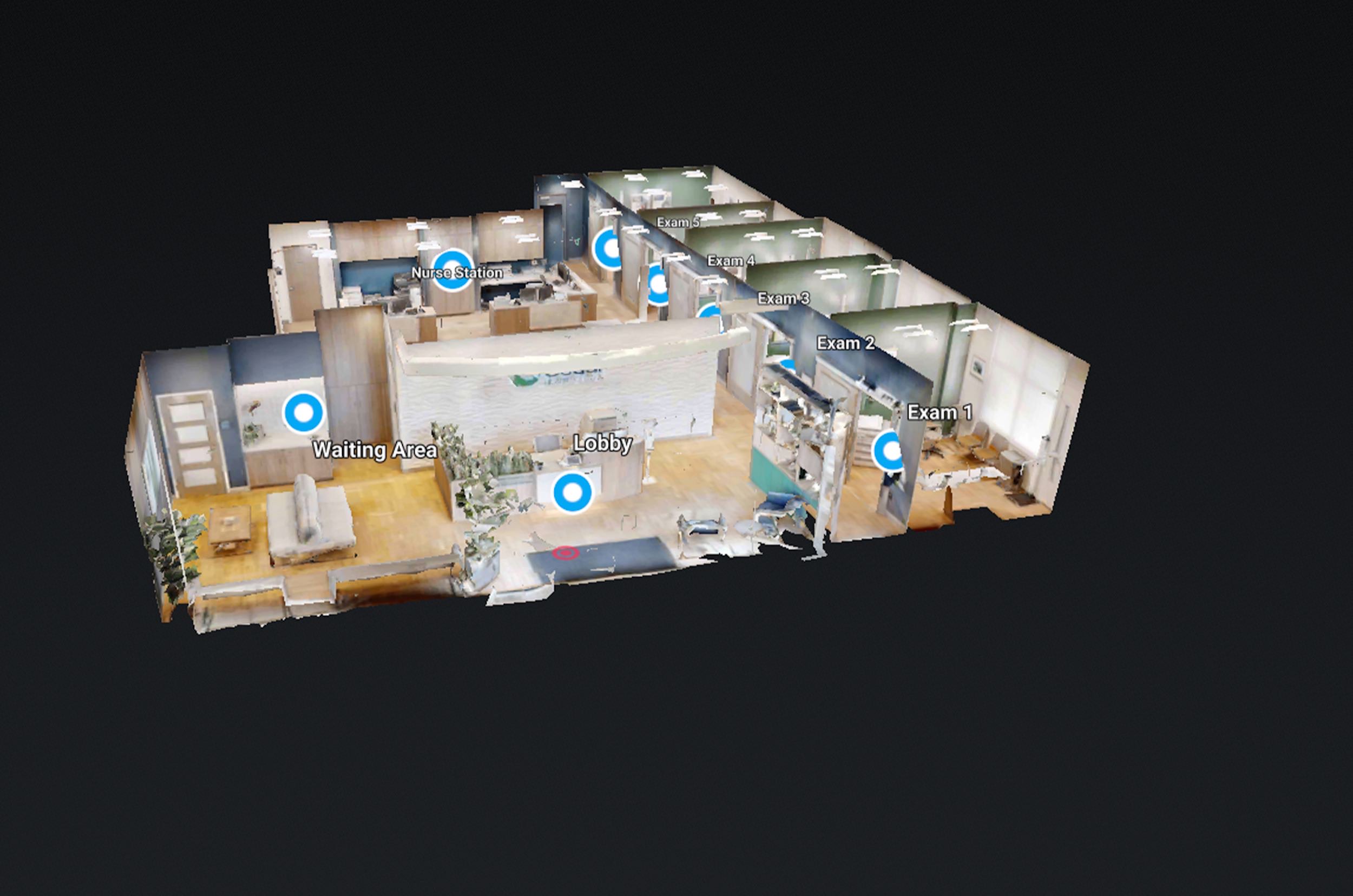

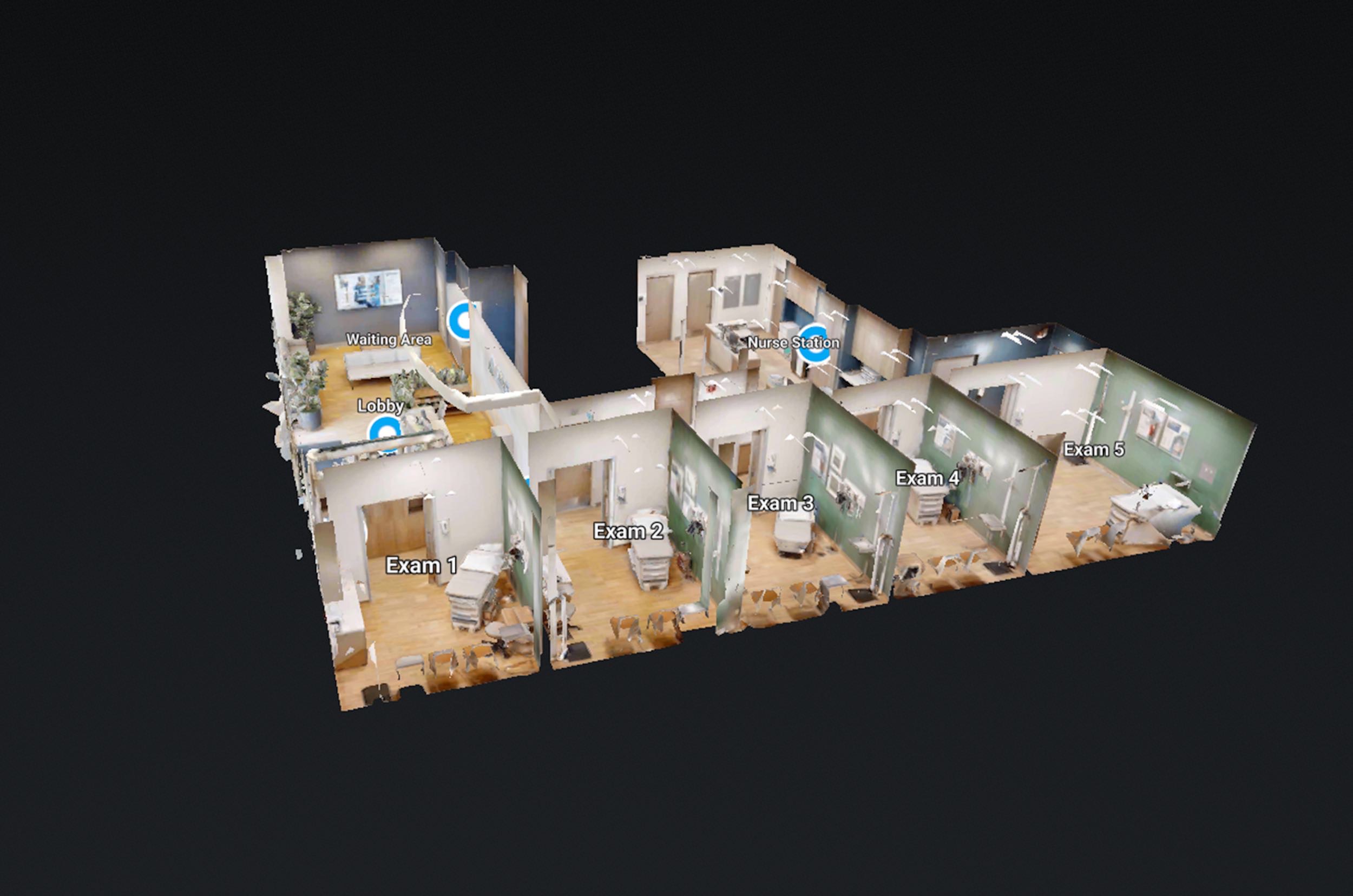

- The overall flow of the space, from room to room

- How big each room felt

- The State of windows, flooring, and fine details such as crown moldings

- The type and condition of appliancesThe number of power outlets in a room

- Quality of light and views from windows

- Just how many people could comfortably fit in a space

- What type of furniture could fit and how it could be arranged

Virtual Tour Users Craved Expert Guidance

Many consumers in the analysis also wished for a traditional, narrated 2D movie as a secondary step (in between viewing a photo gallery and taking a 3D tour) to provide them a guided, expert walkthrough, and get them excited about the space.

Several users noticed that watching a movie involves reduced effort, however, provides similar benefits for understanding the flow of the space and getting to see some detail. They noticed that an expert guide (such as a realtor, wedding planner, museum docent, or even park ranger) could offer up useful information at the right moment — often matters that consumers wouldn’t know to ask.

This desire for credible, expert guidance was pervasive in all kinds of virtual tours — folks wanted someone who had expertise to share the key details about the home, place, artwork, or national park rather than researching by themselves.

Surface-Level Delight Fades Quickly, and Clients Move On

While many of the visually impressive virtual tours elicited a substantial wow factor in research participants, the initial delight quickly subsided. Many users exclaimed,”Oh, this is so cool” mere seconds before closing the tour and moving on to something else, such as a photograph or prerecorded video.

The quick dissipation of superficial delight was most prominent on leisure tours — national parks, art galleries and museums, zoos, tourist attractions, and cultural associations such as the Vatican or Buckingham Palace. Initial excitement was followed quickly with a shrug and dwindling engagement.

The leisure tours that were engaging for the longest were those that restricted the interaction price of consumers and presented a somewhat guided or curated experience. These tended to be 360° movies or photos that offered substantial narrative (either literal audio voiceovers or written text presented at key contextual minutes ).

One of the biggest problems users encountered was slow and difficult movement through the virtual space; turning around in particular was incredibly effortful. For example, a mobile-device consumer”walked” to the bathroom in a virtual house tour and grew frustrated trying to turn around to enter another room.